Tension hangs over corridors

Eco-groups fret over fast-tracking pathways on public lands for power lines and pipelines.

The pipeline in Northern Oregon will result in a linear clearcut across Mt. Hood National Forest.

denver & the west

By Steve Lipsher

The Denver Post

Article Last Updated: 11/18/2007 01:44:18 AM MST

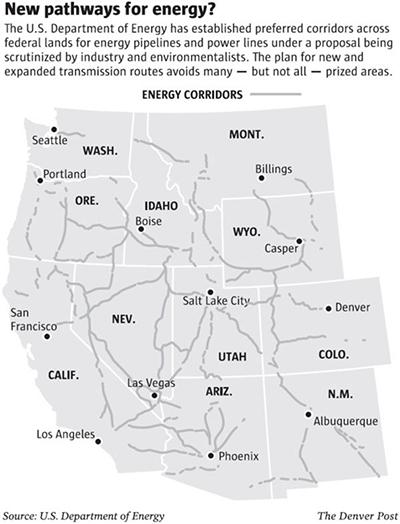

A proposed web of more than 3,700 miles of new pipelines and power lines across the West's public lands - including 420 miles of new or expanded routes in Colorado - is pitting growing energy needs against environmental preservation.

Facing gas and electricity demands projected to increase by 50 percent across the Western United States by 2030, federal energy officials have drawn up a network of preferred corridors across federal lands.

"We want to encourage co-location and use of these corridors so that electrical-transmission lines and pipelines are not ... dispersed across entire landscapes," said Heather Feeney, spokeswoman for the federal Bureau of Land Management.

The plan, however, is drawing fire from environmentalists concerned about marring national forests and national parks with high-tension power lines and wide swaths of land stripped of vegetation for underground pipelines.

"On the map, these look kind of like clean, sterile lines ... going from Point A to Point B," said Liz Thomas of the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance.

"You get on the ground, and it's not like that. There are canyons and mountains," Thomas said. "There's national parks and national monuments, and there's people's favorite hiking and hunting territory."

The Western energy corridor plan, which is up for public comment, would streamline the approval process for energy companies using the preferred 3,500-foot-wide routes on swaths of public land.

Not limited to corridor

Officials say they need to alleviate congestion in power distribution and meet increasing demands by moving greater energy supplies to cities from sources in the Interior West such as hydroelectric plants and natural-gas fields.

While efforts were made to avoid high-value environmental, recreational and scenic areas, the proposal does call for expanded transmission lines adjacent to Utah's Arches National Park and in Colorado's Curecanti National Recreation Area, among other popular recreation areas and scenic landscapes.

Although 72 percent of the designated routes in Colorado run along existing roadways or utility lines, at least 11 segments would cross "sensitive visual resource areas," including the Grand Mesa and the Continental Divide Trail.

Critics say they see the benefit of consolidating transmission routes, but they are wary of the areas that will be sacrificed and concerned that companies would not be restricted to the corridors.

Utilities likely would use the corridors - although they are not required to do so - if they make sense, said Jim Van Someren, a spokesman for Colorado-based Tri-State Generation and Transmission Association.

"It's one more tool," he said. "I don't think it solves all the problems that utilities face ... but it may prove to be helpful in specific instances."

Companies still would be required to undergo environmental reviews for new power lines and pipelines, but they would face only one agency review if they use the established corridors across different jurisdictions of federal lands.

"They're certainly not going to be rubber-stamped just because they're ... proposed to be located in one of these corridors," the BLM's Feeney said.

"Equivalent of a road"

Environmentalists contend that pipelines disrupt the natural environment and fragment wildlife habitat.

"They build this construction corridor, which is basically a travel way for these big Caterpillars and big construction vehicles. It's the equivalent of a road," said Peter Hart, staff attorney for the Wilderness Workshop.

The Carbondale-based environmental organization is battling a current proposal for a new 25-mile pipeline through three roadless areas in the White River and Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre and Gunnison national forests that received final environmental approval on Friday.

"The Forest Service argues that it's not a road," Hart said. "It looks like a road. It smells like a road. It is a road."

The pipeline, said Brad Robinson, president of Gunnison Energy Corp., would follow an existing gas line.

"We would agree we should be limiting the work in a roadless area," Robinson said.

Steve Lipsher: 970-513-9495 or [email protected]

By Steve Lipsher

The Denver Post

Article Last Updated: 11/18/2007 01:44:18 AM MST

A proposed web of more than 3,700 miles of new pipelines and power lines across the West's public lands - including 420 miles of new or expanded routes in Colorado - is pitting growing energy needs against environmental preservation.

Facing gas and electricity demands projected to increase by 50 percent across the Western United States by 2030, federal energy officials have drawn up a network of preferred corridors across federal lands.

"We want to encourage co-location and use of these corridors so that electrical-transmission lines and pipelines are not ... dispersed across entire landscapes," said Heather Feeney, spokeswoman for the federal Bureau of Land Management.

The plan, however, is drawing fire from environmentalists concerned about marring national forests and national parks with high-tension power lines and wide swaths of land stripped of vegetation for underground pipelines.

"On the map, these look kind of like clean, sterile lines ... going from Point A to Point B," said Liz Thomas of the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance.

"You get on the ground, and it's not like that. There are canyons and mountains," Thomas said. "There's national parks and national monuments, and there's people's favorite hiking and hunting territory."

The Western energy corridor plan, which is up for public comment, would streamline the approval process for energy companies using the preferred 3,500-foot-wide routes on swaths of public land.

Not limited to corridor

Officials say they need to alleviate congestion in power distribution and meet increasing demands by moving greater energy supplies to cities from sources in the Interior West such as hydroelectric plants and natural-gas fields.

While efforts were made to avoid high-value environmental, recreational and scenic areas, the proposal does call for expanded transmission lines adjacent to Utah's Arches National Park and in Colorado's Curecanti National Recreation Area, among other popular recreation areas and scenic landscapes.

Although 72 percent of the designated routes in Colorado run along existing roadways or utility lines, at least 11 segments would cross "sensitive visual resource areas," including the Grand Mesa and the Continental Divide Trail.

Critics say they see the benefit of consolidating transmission routes, but they are wary of the areas that will be sacrificed and concerned that companies would not be restricted to the corridors.

Utilities likely would use the corridors - although they are not required to do so - if they make sense, said Jim Van Someren, a spokesman for Colorado-based Tri-State Generation and Transmission Association.

"It's one more tool," he said. "I don't think it solves all the problems that utilities face ... but it may prove to be helpful in specific instances."

Companies still would be required to undergo environmental reviews for new power lines and pipelines, but they would face only one agency review if they use the established corridors across different jurisdictions of federal lands.

"They're certainly not going to be rubber-stamped just because they're ... proposed to be located in one of these corridors," the BLM's Feeney said.

"Equivalent of a road"

Environmentalists contend that pipelines disrupt the natural environment and fragment wildlife habitat.

"They build this construction corridor, which is basically a travel way for these big Caterpillars and big construction vehicles. It's the equivalent of a road," said Peter Hart, staff attorney for the Wilderness Workshop.

The Carbondale-based environmental organization is battling a current proposal for a new 25-mile pipeline through three roadless areas in the White River and Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre and Gunnison national forests that received final environmental approval on Friday.

"The Forest Service argues that it's not a road," Hart said. "It looks like a road. It smells like a road. It is a road."

The pipeline, said Brad Robinson, president of Gunnison Energy Corp., would follow an existing gas line.

"We would agree we should be limiting the work in a roadless area," Robinson said.

Steve Lipsher: 970-513-9495 or [email protected]